* It is a

melancholy object to those, who walk through this great town, or travel in the

country, when they see the streets, the roads and cabbin-doors crowded with beggars

of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children, all in rags, and

importuning every passenger for an alms. [...] their helpless infants [...], as they grow up, either turn

thieves for want of work, or leave their dear native country, to fight for the Pretender

in Spain, or sell themselves to the Barbadoes.

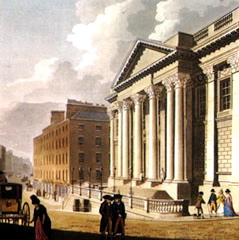

The "great town" is Dublin, Ireland, where Jonathan Swift (1667 - 1745) was born of English parents.

The "great town" is Dublin, Ireland, where Jonathan Swift (1667 - 1745) was born of English parents.

His most famous prose work is the novel Gulliver's Travels (1726), but he was also an essayist and a pamphleteer**.

A Modest Proposal (1729) is the social pamphlet in which he exposes a shocking suggestion to solve the problems of Ireland. Read the passage in which he exposes his proposal in detail.

[...] But my intention is very far from being confined to provide only for the children of professed beggars: it is of a much greater extent, and shall take in the whole number of infants at a certain age, who are born of parents in effect as little able to support them, as those who demand our charity in the streets.

As to my own part, having turned my thoughts for many years, upon this important subject, and maturely weighed the several schemes of our projectors, I have always found them grossly mistaken in their computation. It is true, a child just dropt from its dam, may be supported by her milk, for a solar year, with little other nourishment: at most not above the value of two shillings, which the mother may certainly get, or the value in scraps, by her lawful occupation of begging; and it is exactly at one year old that I propose to provide for them in such a manner, as, instead of being a charge upon their parents, or the parish, or wanting food and raiment for the rest of their lives, they shall, on the contrary, contribute to the feeding, and partly to the clothing of many thousands. [...]

As to my own part, having turned my thoughts for many years, upon this important subject, and maturely weighed the several schemes of our projectors, I have always found them grossly mistaken in their computation. It is true, a child just dropt from its dam, may be supported by her milk, for a solar year, with little other nourishment: at most not above the value of two shillings, which the mother may certainly get, or the value in scraps, by her lawful occupation of begging; and it is exactly at one year old that I propose to provide for them in such a manner, as, instead of being a charge upon their parents, or the parish, or wanting food and raiment for the rest of their lives, they shall, on the contrary, contribute to the feeding, and partly to the clothing of many thousands. [...]

The number of souls in this kingdom being usually reckoned one million and a half, of these I calculate there may be about two hundred thousand couple whose wives are breeders; from which number I subtract thirty thousand couple, who are able to maintain their own children, [...] but this being granted, there will remain an hundred and seventy thousand breeders. I again subtract fifty thousand, for those women [...] whose children die by accident or disease within the year. There only remain an hundred and twenty thousand children of poor parents annually born. The question therefore is, How this number shall be reared, and provided for? which, as I have already said, under the present situation of affairs, is utterly impossible by all the methods hitherto proposed. For we can neither employ them in handicraft or agriculture; we neither build houses, (I mean in the country) nor cultivate land: they can very seldom pick up a livelihood by stealing till they arrive at six years old [...] .

I shall now therefore humbly propose my own thoughts, which I hope will not be liable to the least objection.

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricasie, or a ragoust.

I do therefore humbly offer it to publick consideration, that [the children of parents too poor to bring them up] may, at a year old, be offered in sale to the persons of quality and fortune, through the kingdom, always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump, and fat for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends, and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt, will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter. [...]

I have already computed the charge of nursing a beggar’s child (in which list I reckon all cottagers, labourers, and four-fifths of the farmers) to be about two shillings per annum, rags included; and I believe no gentleman would repine to give ten shillings for the carcass of a good fat child, which, as I have said, will make four dishes of excellent nutritive meat, when he hath only some particular friend, or his own family to dine with him. Thus the squire will learn to be a good landlord, and grow popular among his tenants, the mother will have eight shillings neat profit, and be fit for work till she produces another child. [...]

*

This and the following extracts: Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal, 1729. Web

edition published by eBooks@Adelaide. Rendered into

HTML by Steve Thomas. Published by eBooks@Adelaide, 2012. Licensed under Creative Commons Licence.

** An unbound publication (that is, the pages are not stitched the one to the other), made of one page, printed on both sides, or of a larger page folded in half, thirds, fourths, and without a cover. Especially in the 16th-18th century they were used to diffuse political, social, religious ideas in a more rapid and extensive way than books.

Girl with a Basket of Pamphlets, oil on paper, by French School.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Girl_with_a_Basket_of_Pamphlets.jpg

** An unbound publication (that is, the pages are not stitched the one to the other), made of one page, printed on both sides, or of a larger page folded in half, thirds, fourths, and without a cover. Especially in the 16th-18th century they were used to diffuse political, social, religious ideas in a more rapid and extensive way than books.

Girl with a Basket of Pamphlets, oil on paper, by French School.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Girl_with_a_Basket_of_Pamphlets.jpg